Just days away from 2025. We are all operating in a high-pressure environment.

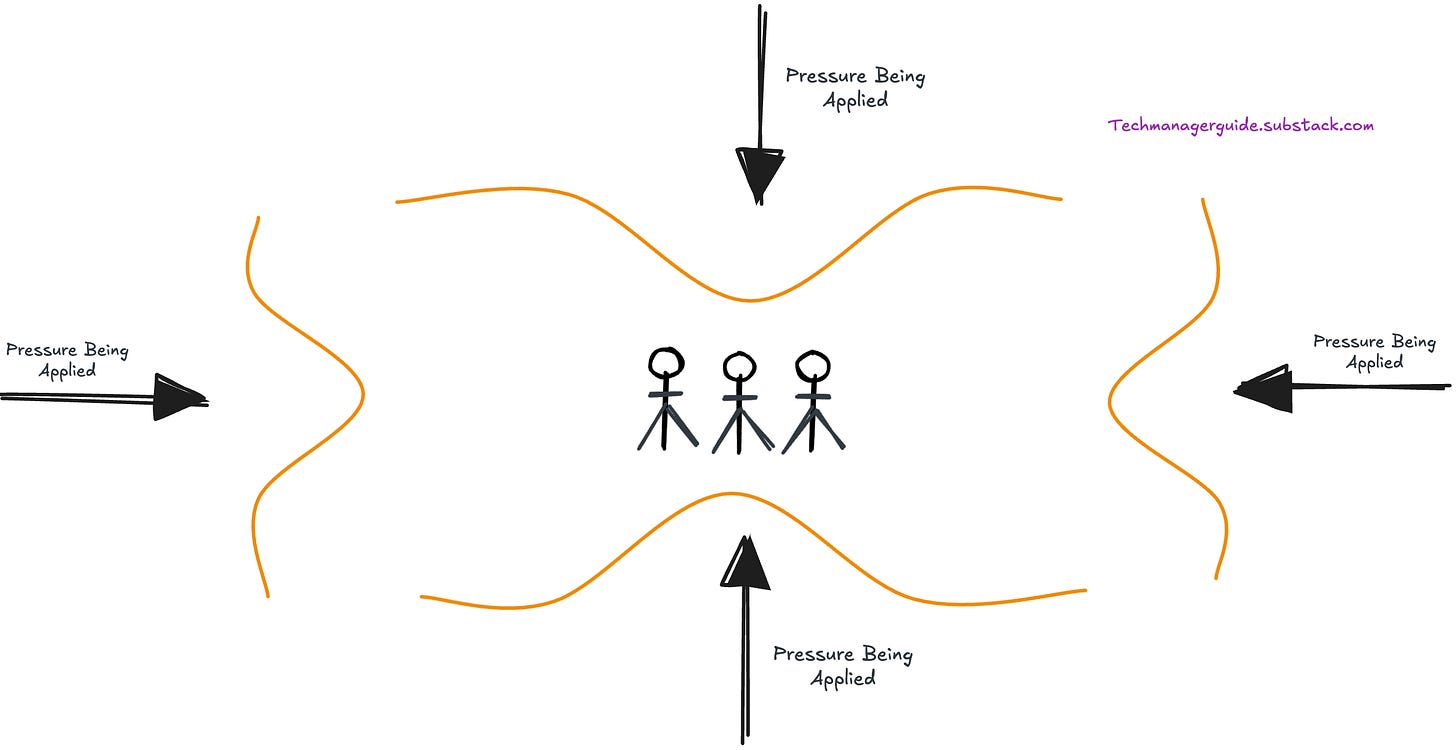

Engineering teams are expected to deliver more, and team leads are expected to give their all. There’s a pressure to deliver software on time with less resources than before, at the same time with a good quality. Pressure to meet stakeholder’s expectations. Pressure to deliver outcomes and create impact not just outputs. Pressure on you to balance hands-on contributions with managerial duties—And you name it.

As an engineering manager, you serve as a catalyst in helping your teams navigate this pressure. But are you up for it? How much pressure can you handle, and how can you help your team work with it rather than ignoring it? Is pressure always a negative force, or can teams still thrive under it?

In this edition, we’ll explore how you can pragmatically approach pressure situations as an engineering manager and turn them to your and your team’s advantage.

Me feeling the pressure for the first time

When I first experienced pressure early in my software engineering career, it was overwhelming. I felt immobilized, like I was sinking into quicksand, unsure of how to move forward.

A critical bug emerged in production as a result of my deployment, bringing the entire banking application down. Users couldn’t make transactions and that was enough to trigger panic. You can imagine the pressure—it’s a financial system, and downtime means lost transactions and trust. Our delivery manager was overwhelmed with client complaints, and our team lead was under immense pressure to get the system back online fast.

Meanwhile, I was just a few weeks into the role. The weight of responsibility hit me hard—I was still reeling from how the issue happened in the first place. But I didn’t have the luxury of time to dwell on it; I had to fix the issue, and quickly. It was the first time I fully realized the immense responsibility of engineering in a high-stakes environment and how the pressure doesn't just stem from fixing things—it comes from the fear of failure and its far-reaching consequences.

Another pressure situation I recall involving our team being in a fire-fighting 🧯🔥 mode for nearly six months. We were under immense pressure to deliver a major software project, with upper management constantly breathing down our neck. We ended up overrunning our original deadline by eight months—yes, eight months. The stress was overwhelming. Meetings piled up, more engineers were pulled in from neighboring teams, but despite the extra hands, the pressure never eased. It felt like a race against time, yet we were always behind, struggling to keep up with expectations.

This scenario wasn’t just a matter of deadlines; it was an all-consuming challenge where everyone felt the burden. The pressure from management and the fear of failure seeped into our daily work, leading to burnout and a constant reactive mindset. It became harder to focus on solutions or even think creatively. Instead, we were stuck in a loop of reacting to problems as they arose.

Lead’s role in pressure situations

Pressure we experience is partly self-induced and partly from people around us and above. I remember one situation when my team lead, under immense stress, panicked during a critical production outage. He lost his cool and started yelling at the team to "fix it immediately," without giving clear guidance. His panic spread, making the situation worse as we fumbled under the weight of his pressure. It just didn’t help but made the team more anxious and hindered our ability to think clearly.

I realized the role that team leads play in pressure situations is crucial. A team lead's response can either help stabilize the team or exacerbate the stress. In high-pressure environments, team members look to their leader for guidance and composure. When a lead maintains a calm and focused demeanor, it instills confidence in the team, even when the situation seems overwhelming. Conversely, if the lead panics or loses control, it amplifies the team's anxiety, hindering their ability to solve problems effectively.

Good leaders manage the pressure not only by keeping the team on track but also by creating a sense of structure amidst the chaos. They set clear priorities, delegate tasks thoughtfully, and provide the necessary support. They also shield the team from unnecessary distractions, like micromanagement from higher-ups, allowing engineers to focus on their work.

Bad Pressure

Pressure that I experienced and what we commonly refer to in a work environment are all “bad pressures”. Bad pressures are the ones that create stress and anxiety. That lets someone overwork, burnout or even quit their jobs if it goes out of their hand. Great resignation that happened in 2021 is a great example of this, where feeling pressured was one of the key reasons for the mass resignation.

Some forms of bad pressure includes:

Competition within the team: Internal competition within the team can create a toxic environment where team members feel the need to outperform one another. This undermines collaboration and erodes trust, leading to stress and anxiety.

Unrealistic expectations from upper management or stakeholders: Pressure arises when leadership demands more than what is feasible, setting unattainable goals or shrinking timelines. This creates constant stress and can result in burnout, diminishing productivity and morale.

Micromanaging your team and not trusting their expertise: Constantly second-guessing or hovering over team members without allowing autonomy leads to frustration. This lack of trust undermines their confidence and stifles creativity, adding unnecessary pressure.

Fear when there’s a mistake/failure: Creating a blame culture where mistakes are punished fosters fear. Team members become overly cautious, afraid to take risks or innovate, which hampers progress and adds immense psychological pressure.

Heavy reliance on a star performer: When one person is consistently burdened with critical tasks, it can lead to exhaustion and burnout for that individual, while also demoralizing the rest of the team, who may feel undervalued.

Constant firefighting: Operating in a reactive mode with continuous crisis management prevents the team from focusing on long-term goals, leading to chronic stress. This leaves no room for improvement or innovation, only survival mode.

In most of the cases, it is us, engineering managers, who create bad pressure in our teams or at least responsible for it, even though we aren't the ones who directly induced it. This happens when we accept unrealistic expectations in an effort to impress stakeholders or leadership, rely too heavily on a star performer to do all the heavy lifting for you and your team to succeed in the near term, or allow a blame culture to thrive within the team. In all these situations, our actions or lack of intervention contribute to the pressure and its negative impact on the team’s well-being and performance.

What can you do to avoid bad pressures in your teams?

Push back on unrealistic expectations: As an engineering manager, it’s essential to challenge expectations that aren’t feasible. This involves having honest conversations with stakeholders / leadership about what’s realistic, ensuring that deadlines and project scopes are achievable without sacrificing quality or team well-being. Pushing back helps set clear boundaries and fosters healthier expectations for everyone involved.

Let your team commit but learn from mistakes: Mistakes are inevitable in software engineering. It’s crucial to provide guidance, reflect on what went wrong, and ensure that the team learns from each experience. This creates a culture where mistakes are viewed as learning opportunities, not as failures that teams fear to commit for.

Team orientation than self: It’s important to foster a collaborative culture where every team member’s contributions are valued. Avoid creating a situation where one person is overburdened as the ‘star performer.’ Instead, focus on collective team goals, ensuring that all members work together, share responsibility, and support each other’s growth, which reduces internal competition and fosters a more positive, balanced work environment.

Be strategic instead of firefighting: Instead of constantly reacting to issues as they arise, focus on long-term strategies that minimize chaos and reduce urgent, last-minute crises. Planning ahead, prioritizing tasks, and building systems that are resilient will help avoid the need for constant firefighting, allowing the team to work more efficiently and sustainably over time.

Good Pressure

Heard about good fat vs. bad fat?—Good pressure is of that sort. Unlike bad pressure, which can overwhelm and cause stress, good pressure motivates individuals to perform at their best, helping them reach newer heights. It challenges them to step out of their comfort zone, fostering growth and development.

Athletes are prime examples of performing well under the right kind of pressure. It drives them to achieve new milestones they never imagined. Take Usain Bolt, for instance. He understood the stakes, and that awareness fueled his incredible performances. During the 2009 Berlin World Championships, he broke his own 100m world record, finishing in 9.58 seconds. Competing with world-class athletes pushed him to fine-tune his technique and sharpen his focus, demonstrating how the right environment can lead to continual self-improvement.

Some forms of good pressure includes:

Challenging but rewarding projects: These projects push engineers to stretch their skills, learn new things, and solve complex problems. The difficulty is balanced by the sense of achievement and value once the project is completed successfully.

Continuous improvement in delivery cadence: Encouraging the team to deliver faster without sacrificing quality can be a positive motivator, promoting efficiency and process optimization, while ensuring continuous progress.

Work with changes and uncertainties: Navigating uncertainty and changes in scope (but not too frequent—you have to find that balance) or direction challenges engineers to become more adaptable, sharpening their problem-solving and decision-making skills.

Set high benchmarks and push for excellence: Pushing your team to achieve higher standards in the technical aspects of their work ensures they continually refine their coding practices, optimize performance, and build scalable systems. The pressure to maintain technical excellence motivates them to stay sharp and grow their expertise.

As an engineering manager, it's crucial to keep the “good” pressure on. This type of pressure encourages your team to embrace challenges, pushing them to develop resilience and achieve growth without feeling overwhelmed. Good pressure helps engineers strive for higher performance, meet ambitious targets, and improve continuously. In today's fast-paced environment, engineering teams need this to not only meet organizational goals but also to surpass them. Without this positive force, teams risk falling short of the evolving expectations and ambitions of the bigger picture they are part of.

Now think about your teams—what pressure are you creating? Bad pressure? or Good pressure? How is it affecting your team, positively or negatively? Let me know in the comments—would love to hear your thoughts and experience.

In the next edition, we'll explore how engineering teams perceive pressure and how it spreads across the organization, passed from one level to the next and among peers.